Condition 003

Illumination before Elimination;

Don’t remove something before you understand it.

Last spring, feeling overwhelmed, I eliminated my vegetable garden entirely. It seemed non-essential—after all, I can buy food at the store. Now having gone a season without a vegetable garden, I realize what I’d lost: mental restoration, physical connection to nature, and a quiet space for reflection. I’d removed something essential in my quest for simplicity.

This pattern repeats everywhere: software features cut for “streamlining” that users relied upon, education reduced to metrics that miss the richness of learning, DOGE eliminating roles without understanding their connective functions or the downstream effects. We eliminate the necessary complexity because we can’t tell the difference between what is necessary and what is superfluous.

The quest for clarity must precede the quest for simplicity.

What has promised simplicity, but has let you down when you try to use it?

Can you put your finger on a small part of why it falls short?

Complex systems (think ecosystems, with necessarily interconnected elements) differ fundamentally from merely complicated ones (think mechanisms, with many independent parts). When we apply simplification to complex systems–organizations, ecosystems, relationships– we risk destroying what makes them function.

Instead of jumping to elimination, we need to first illuminate–through visualization–what is necessary.

Visualization transforms invisible complexity into navigable terrain. I start with a simple “Is it like this?” approach, drawing what I understand about a situation, however incompletely. This visual anchor gives us the tool to determine what is essential before we take decisive action.

When you make complexity visible, you receive the confidence to navigate it, rather than the anxiety that comes from avoiding what feels overwhelming. The goal isn’t perfection—it’s starting the visual dialogue that transforms overwhelm into clarity.

Thanks for reading,

Confident Moves

Try this in less than 10 minutes:

Think of a situation where you feel torn between two good things—where “simplifying” isn’t an option.

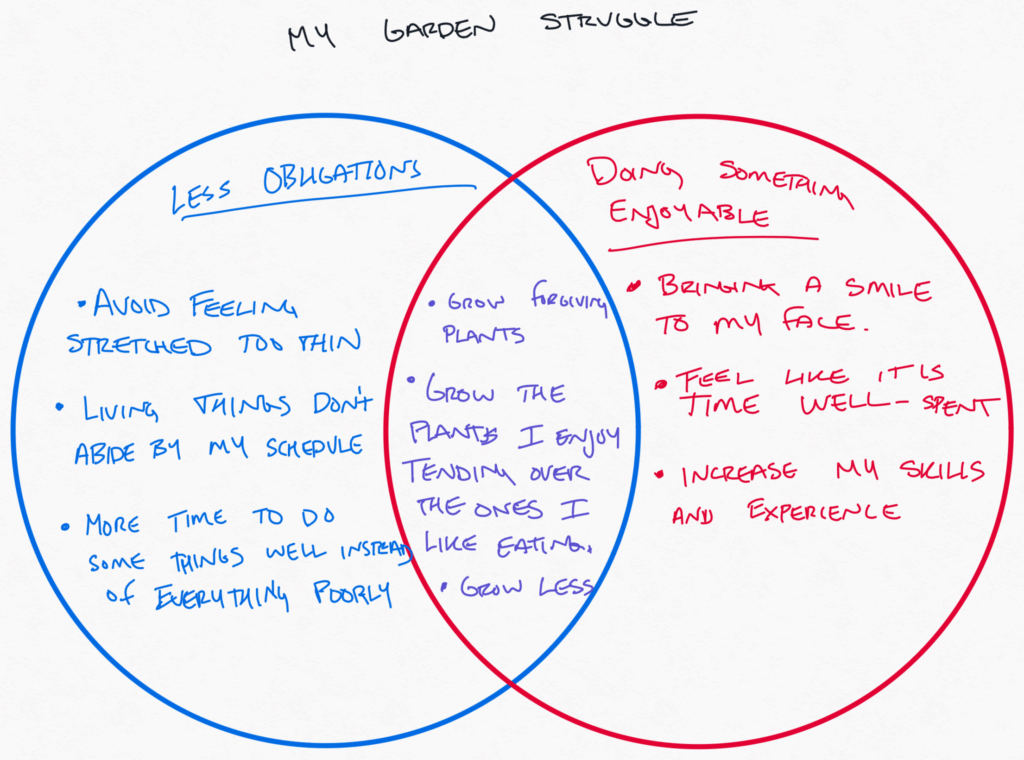

I chose two good things that I want: Less Obligations and Doing Something Enjoyable (see the Venn diagram above)

- Draw two overlapping circles on a blank page

The physical act of drawing engages different thinking pathways than mental reflection alone. - In the left circle, write what you want to preserve

What’s the value, quality, or outcome that feels essential?

What would be lost if it were removed? - In the right circle, write the competing need

What’s the other necessary quality that seems in tension with the first? What makes this situation complex rather than merely complicated? - In the overlap, explore possible integrations

Instead of choosing one over the other, what might honor both needs? - Step back and ask, “is it really like this?”

Does it feel like you’ve captured what made it feel difficult?